The rise of US biscuits

Biscuits, like the banjo, have a complex lineage. Their roots lie in dry, twice-baked breads, or rusks, that the British called “bisquites” after the Latin phrase panis bicoctus, or “twice-baked bread”. But in the American South, particularly in the hands of Black cooks, they became soft, leavened symbols of class, skill and Southern identity.

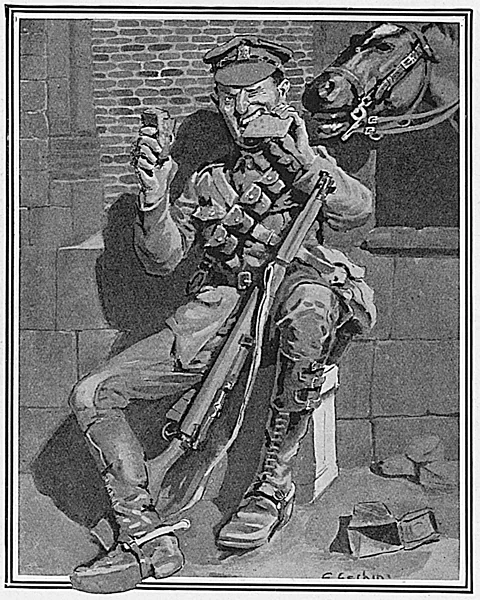

In the book The Biscuit: The History of a Very British Indulgence, Lizzie Collingham writes that biscuits were an “an indispensable tool of empire building”. Indeed, these nonperishable breads sustained soldiers and sailors for millennia, and in the early 1600s, English settlers in Jamestown, Virginia, survived on a supply of biscuits brought from the motherland.

Alamy

AlamyA distinctly Southern biscuit began to emerge in the 18th Century. On Royal Navy ships, tough, dry biscuits had earned the nickname “purser’s nuts”. But in finer settings on both sides of the Atlantic, bakers added sugar, citrus and spices. The Virginia Housewife, an 1824 cookbook by Mary Randolph, includes a recipe for Tavern Biscuits, whose ingredients included flour, sugar, butter, mace, nutmeg, brandy and milk. It also shared a recipe for beaten biscuits.

“[Beaten biscuits] were the most common biscuit in the South,” said Michael Twitty, a James Beard Award-winning food writer and historian. “The lore behind them is true. A Black child, normally a little boy, would sit there with the back of an axe or a club, and on a clean log, he would literally beat this dough over 1,000 times.”

The thin, crunchy beaten biscuit closely resembled what Americans consider a cracker, but this violent, repetitive thrashing – only possible with enslaved labour – produced a slight rise and delicate crumb onto which diners would drape slices of country ham. White flour was still a luxury in the antebellum South, and beaten biscuits were an edible stamp of wealth.

“Biscuits have been a demarcation line in terms of class and race,” said Toni Tipton-Martin, a food journalist and historian whose work includes the book The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks. “African Americans have traditionally been known for making cornmeal and more coarse grain breads. Wheat flour was not available in early America, and it was an expression of affluence to be able to make biscuits.”

Melanie Wilkerson

Melanie WilkersonHowever, it was chemical leavening agents that created the soft, layered Southern biscuit as we know it today. At first, bakers used saleratus (potassium bicarbonate) and soda (sodium bicarbonate). The buttermilk in Giddens’ recipe dates to these early leavening agents, which required an acid to activate. Then in 1856, Eben Norton Horsford patented baking powder, officially giving rise to the poof of the Southern biscuit.

As milling technology improved in the late 19th Century, Southern-grown soft winter wheat, (which was better for so-called “quick breads” than sturdy loaves) gained popularity. When flour prices dropped, biscuits became a marker of social mobility across racial lines, transforming a Sunday treat into an everyday staple.